Louisville’s First Sewers & Sewage Treatment Plant

Home About Us Louisville’s First Sewers & Sewage Treatment Plant

The Louisville Metro combined sewer system was built from the 1860s to the 1950s; while the Louisville-Jefferson County Metropolitan Sewer District was founded in 1946 by the Kentucky State Legislature. Our sewer system dates back to the 19th Century, and many of the original sewers are still in use today.

For its first 40 years, Louisville had no sewers and no drainage system. Sanitary waste went into outhouses; washwater was dumped into yards, streets and alleys; rainwater eventually found its way into streams and the Ohio River. In the flat areas of the city, much of the water simply stayed, forming large, stagnant ponds that bred mosquitoes that spread disease.

In the 1820s, the city started digging ditches to drain the ponds; over the years, underground drainage pipes were added. This first drainage system took the water directly to small streams and to the Ohio River.

The Louisville Water Company opened for business in 1860, bringing running water to the city. Running water brought “indoor plumbing,” and the need for a way to dispose of the water after it was used. The solution seemed simple: build wastewater lines and connect them to the city’s drainage system to carry the wastewater and stormwater away. This is the very beginnings of combined sewers, which were “state of the art” engineering in 1860.

It wasn’t long before the streams stank with sewage. The situation was especially bad in dry weather, when sewage was often the only water flowing in the small streams.

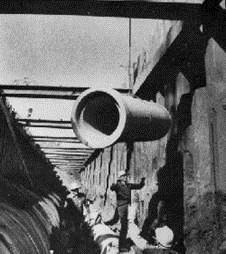

The early solution to this problem was the interceptor sewer, designed to “intercept” the sanitary sewage before it could reach the streams, transporting it to the Ohio River instead. The interceptors were designed to carry the normal load of sanitary sewage — but not the large amounts of additional water from rainfall. To prevent the large stormwater flows from backing up into people’s homes, combined sewer overflows (CSOs) structures were installed along the interceptors to allow excess water to flow into the streams when it rained.

This was a great improvement. In dry weather, the streams looked and smelled much better. When it rained, the rainwater diluted the sanitary sewage and helped carry the overflow away. The streams were still polluted, but not nearly as much as before. And they didn’t spread as much disease.