The Challenge of Separate Sewer Overflows

Home About Us The Challenge of Separate Sewer Overflows

The practice of combining sanitary sewage and storm water draining in a single pipe was common until the late 1950’s. The state of Kentucky banned the construction of combined sewers in 1955. Since that time only separate sanitary sewer systems and separate stormwater drainage systems have been built.

Suburban expansion was booming from the 1950s through the 1970s. MSD had the authority to serve the entire county, but financially was only able to provide sewer service to the city limits. The Jefferson County Board of Health allowed individual septic tanks where the land could accommodate them, and required small, “package” sewage treatment plants where septic tanks wouldn’t work well. The Board emphasized that both of these measures would be considered “temporary,” and would be replaced by MSD service when MSD sewers became available. This compromise would be another long-simmering source of controversy; many of these “temporary” facilities would be built without following solid construction guidelines and would still be in use more than 40 years later.

In 1964, a masterplan was developed for Jefferson County that recommended MSD provide service outside the city boundary. The plan also recommended that MSD take over small sewer systems, and the “temporary” treatment plants, as its service area reached them. When MSD started expanding its service area to accommodate this, there were about 350 small treatment plants in Jefferson County. During the preceding year, nearly half the 326 plants inspected by the health department had gotten “poor” ratings for inadequate maintenance or improper operation.

In late 1984, the Jefferson County health department released a study showing that all major streams in Jefferson County were unsafe for swimming; small treatment plants and septic tank systems were blamed. The state of Kentucky gave the owners of 14 small plants in the West County area until April, 1985 to shut down; at least half were violating their permits, and some had never bothered to obtain permits — a clear violation of state and federal environmental laws.

With the Environmental Protection Agency, MSD revised and updated the sewer expansion plans. By the mid-1980s, there had been a broad community consensus that a countywide sanitary sewer system would be best for the environment, for economic development, and for quality of life. The challenge was to correct the mistakes of the past by eliminating existing small treatment plants and septic tank systems, and by providing sewers for new development. Construction proceeded rapidly.

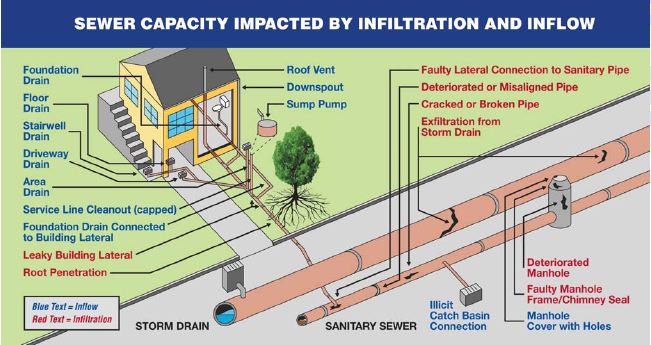

One of the major challenges facing MSD through the years has been correcting problems with old and improperly constructed sewer lines. The problems fall into two basic categories: deterioration and improper connections – wet weather aggravates both.

As sewer lines age and deteriorate, cracks develop. Groundwater can leak into the sewer lines through these cracks — a condition called infiltration. Infiltration has been a serious problem in many subdivisions with sanitary-only sewer lines. Water leaking into the lines can quickly overload them, causing backups into basements.

The second basic problem, inflow, is caused by improper stormwater connections to the sanitary-only sewers. Approximately 50% of the stormwater entering the sanitary sewer comes from private property sources. Downspouts and basement sump pumps are the major offenders; driveway and walkway drains also cause problems.

While the sanitary sewers are not intended to carry other flows, groundwater and stormwater can infiltrate the sanitary sewers through cracks in deteriorated lines, tree root damage and sump pumps, roof drains and foundation drains illegally-connected to the sanitary sewer system from individual properties. This entry of unintended water to the sewer systems uses pipe capacity intended for wastewater and can ultimately result in sanitary sewer overflows (SSOs).